(Article originally published here)

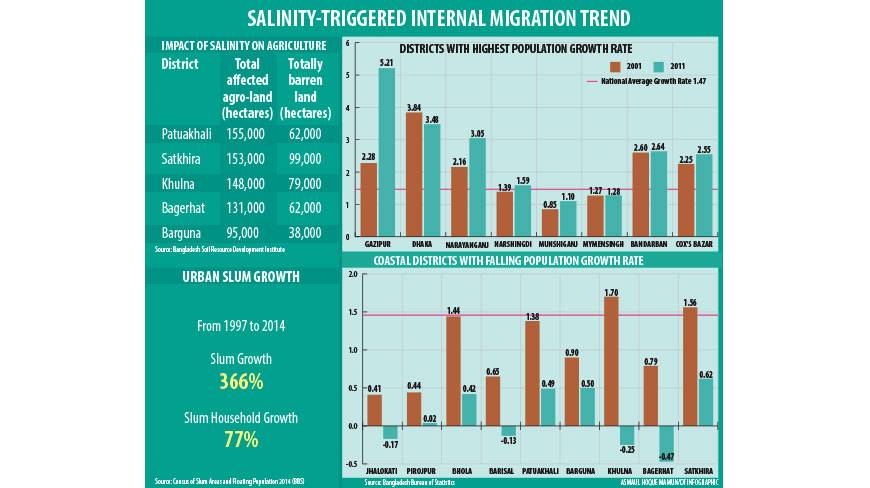

Population growth rates in some of the worst salinity-hit coastal districts of Bangladesh have become negative, coupled with a staggering growth in slums, point at a mass exodus of agro-based people towards the urban areas.

The alarming intrusion of salinity into vast tracts of arable land in these districts can be directly linked to the global climate change – the climbing world temperature and the consequent rise in sea level.

According to the last population census conducted in 2011, the average population growth rate in Bangladesh was 1.47, which 10 years ago was 1.58.

However, compared to this figure, the worst victim districts of salinity display negative population growth rate – Jhalakathi -0.17, Barisal -0.13, Khulna -0.25 and Bagerhat -0.47.

In fact, population growth rates in most other districts in Bangladesh’s coastal belt have also drastically fallen.

During the same period, the slums in the country’s urban areas have inflated. Experts say that a significant portion of the new slum population comprise of displaced agro-based people from some of these coastal districts.

The government of Bangladesh has achieved some degree of success in controlling overall population growth during 2001-2011, which is reflected in the falling average rate. But there is no reason to think that the negative growth rates in these districts indicates greater success in birth control.

In fact, salinity intrusion triggered by rising sea level has badly affected vast stretches of arable land in coastal districts, rendering significant portions completely barren.

For example, in Khulna and Bagerhat, 148,000 and 131,000 hectares of land respectively have been affected by salinity. Of these, 79,000 hectares in Khulna and 62,000 hectares in Bagerhat have been turned completely barren – meaning nothing can be grown on these lands.

As a result, a vast section of people living in these areas were left with nothing to do but migrate to the city areas and live in sub-human conditions in the slums of the metropolitan cities such as Dhaka and Chittagong.

Hydrology expert Prof Ainun Nishat said: “The fall in population growth rate in these areas does not mean that birth rate has been lower. Rather, it points at massive internal migration by people who seek employment because economic activities, especially agriculture, have been severely affected by gradually increasing salinity in the regions’ water and land.”

According to the Census of Slum Areas and Floating Population 2014, there has been a 77% rise in the number of slum households in the country in the 17 years from 1997 to 2014. During the same period, the number of slums increased by a staggering 366%.

Noted urban planner and slum researcher Prof Nazrul Islam said: “Migration from some of the coastal districts such as Khulna, Shatkhira and Bagerhat to the urban areas is a new trend triggered by a loss of livelihood because of salinity intrusion.”

Case 1

Having struggled nearly a decade with salinity intrusion, Sirajul Islam Morol, a 50-year-old farmer from Shatkhira, eventually moved to Dhaka with his five-member family in 2011.

Now he pulls rickshaw and lives in a 100 sq-ft shanty in the Doaripara slum in the Mirpur area, one of the biggest slums in Dhaka city.

Back at his home in Shatkhira, he still owns a two-acre land on which he used to cultivate paddy and shifted to shrimp cultivation after salinity intrusion began. At one point in the last decade, even cultivating shrimp became impossible.

Now, his land has been turned completely barren by salinity.

“Everything is affected by salinity – from agricultural land to drinking water – everything,” said a frustrated Sirajul.

“If everything was okay back at home, I would have never come to Dhaka. The life I am leading now is both frustrating and disgraceful. We now have share a toilet and kitchen with 15 other families,” he said with eyes suddenly nostalgic from the memories of an affluent past.

Having struggled nearly a decade with salinity intrusion, Sirajul Islam Morol, a 50-year-old farmer from Shatkhira, eventually moved to Dhaka with his five-member family in 2011. Now he pulls rickshaw and lives in a 100 sq-ft shanty in the Doaripara slum in the Mirpur area, one of the biggest slums in Dhaka city Photo: Mahmud Hossain Opu

Case 2

Shafiqul Islam, 50, is another climate refugee from the district of Bagerhat, who came to Dhaka three months ago.

He also pulls rickshaw for earning a living for his four-member family who lives in the Shat-Tola slum, also one of the biggest slums in the capital city.

“Even 10/15 years ago, the scarcity of drinking water was not so acute. My wife used to fetch water for daily use from a pond located some 500m from our homestead. But in the recent years, salinity has rendered the water in that pond unusable,” said Shafiqul when asked he had migrated to Dhaka.

“The one-acre land that I owned back at home had been turned completely futile over the last fews years. Not a single crop could be grown there. Ten years ago, I used go grow paddy. But as salinity crept in, I had to shift towards shrimp cultivation. But over the last two years, that too became hard because of various diseases.

“In the last one year, a Tk1.32 lakh investment fetched me only Tk3,000. That was like the last nail in the coffin, leaving me with no option but to migrate to Dhaka for survival,” Shafiqul said.

Way out

According to the 5th Assessment Report of the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Bangladesh is identified as being at specific risk from climate change due to its exposure to sea-level rise and extreme events like salinity intrusion, drought, erratic rainfall and tidal surge.

Climate change expert Saleemul Huq said there are both economic and climatic reasons behind the internal migration and displacement.

“People have been migrating due to a lack of fresh water source, erratic weather pattern and salinity, which destroyed agricultural production and practices,” Saleemul said.

One way of giving the huge populace their likelihood back could be developing salinity tolerant varieties of crops, particularly rice.

However, researchers say none of the existing varieties of salinity-tolerant rice can stand the level of salinity that has affected some of the coastal districts.

According to Jiban Krishna Biswas, director general of Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI), paddy can be made tolerant to 12dS/M of salinity, at best.

But studies have shown that salinity in more than half of the arable lands in five coastal districts have gone well past that level.

Another way out could be reducing salinity in the coastal rivers by increasing the flow of sweet water from the upstream.

Hydrology expert Prof Ainun Nishat said: “Since the 70s, after the Farakka Barrage was built on Ganges, Bangladesh has not been getting enough water during the lean period. If we got more water in the Ganges basin, the coastal rivers would have got more sweet water and thus, over a period of a few years, the excess salinity could be washed away from agro-land.”

Written by: Abu Bakar Siddique, Environment Reporter, Dhaka Tribune