- Rural to urban climate-linked displacement is increasing worldwide, stretching urban slum capacity

- Conditions in Dhaka’s temporary settlements in the slums are inhuman, with poor access to basic services

- In the short term, investment is needed to make conditions liveable in the slums

- In the long term, a robust protection framework that centres community participation is essential to preserve human rights within forced climate displacement

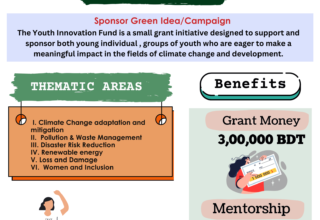

Despite promising steps taken at COP26 in Glasgow last November, the world is off track to close the gap to limit global temperatures to 1.5°C. There is a growing consensus that a failure to do this is not only an environmental issue, but a human rights issue too, and has been officially recognised as such (UN Human Rights Council Resolution 48/13) (1) .

On the current trajectory, it is estimated that in 2050, 4.7 billion people will reside in countries with high and extreme ecological threats, equivalent to 48.7% of the world’s total population (2). Considerable literature suggests that it’s the poorest and most vulnerable groups – often concentrated in the developing world – who will be disproportionately represented in this statistic, for reasons including weak socio-economic structures, high natural resource dependency, and high levels of disenfranchisement, discrimination, and marginalisation (3) (4).

Climate mobility in Bangladesh

With high ecological threats come an increased risk of displacement, as homes and livelihoods cease to be viable. The Bangladeshi Government has acknowledged that by 2050, one in every seven people in Bangladesh will be displaced by climate change (5).

People’s decisions to leave their homes vary incredibly widely, making determining the causality between economic “pull” and environmental “push” highly subjective (6). Climate mobility is no exception. Part of a complex pattern of multiple causality, climate mobility drivers are often closely linked to economic, social and political ones too (7).

Every year, an estimated 500,000 people in Bangladesh move from rural areas to Dhaka (8). This movement, which began to pick up speed after the liberation of Bangladesh in 1971, was characterised by migrants building homes illegally on Government (‘Khas’) land. Several decades on, this land is now vastly overcrowded and largely controlled by ‘gatekeepers’: powerful, unelected individuals within the slums who control many of the decisions around housing, rent and (illegal) access to utilities (9). With no unoccupied land available to build a home, new entrants find themselves forced to pay extremely high rents – sometimes more per sq. ft. than Dhaka’s affluent areas (10). In 2018 it was estimated that 47% of the Bangladeshi population now lives in slums or urban informal settlements (11).

Living conditions in informal settlements

The living conditions in these settlements are poor. The housing is dense, with very low structural quality. Residents describe life there as “inhuman”, with a typical living space being one 10ft x 10ft room for five to six people, with no air circulation.

During the summer, as in many urban settings, the slums become Urban Heat Islands (UHI) – but their unique characteristics mean that residents experience disproportionate, often highly damaging impacts. Amongst the many effects of prolonged exposure to high temperatures are vomiting, fainting, skin rash, heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and death (12). This is exacerbated when high temperatures combine with high humidity.

Most informal settlements in Dhaka are near wetlands or lakes. However, due to an absence of flood embankments and a proper drainage system they are often badly flooded during the monsoons, which increases the risk of waterlogging. Around 30–40% of Dhaka is characterised as a highly or very highly vulnerable zone with respect to waterlogging, wherein informal settlements represent approximately 70% (13).

Photo Source: Henrietta

Access to basic services

Alongside this, people living in the Dhaka slums often do not have access to basic services, such as water, sanitation and electricity. Where they do, most of the connections are illegal.

Households tend to collect water from communal water points. Families are charged a flat fee of around $2.5-6 per month, despite water only running for around 2-3 hours per day. They are also charged around $1-2.5 per month for toilet access, with up to 30 families sharing a facility.

The illegal electricity connections are provided by the gatekeepers, with average monthly costs of $2.15 per light (bulb) and $10 for a fridge. For cooking, good gas pressure is often only found early in the morning or late at night; the charge is $7 per month for a single stove.

Residents tell of how they have repeatedly asked the government to provide them with legal access to basic services to help cut down their expenses and improve their quality of life, to no avail. “The authorities don’t ask us what we need. They never ask.”

The Bangladeshi Government has, over the years, developed a number of policies for informal settlements. A 2012 National Strategy for Water and Sanitation, for example, mandates that all basic services must be made accessible to slum dwellers irrespective of legal status (14) – and the 2020 update of the 2005 Pro-Poor Strategy for Water supply and Sanitation in Bangladesh underscores this, placing emphasis on SDG6: to ensure the availability and sustainable management of safe water and sanitation for all – “leaving no one behind” (15). On a larger scale, the 2016 National Housing Policy proposes starting a major programme of slum ‘shifting’ – or resident rehabilitation (16).

However, these policies have not yet been implemented on the ground. Because these are illegal settlements, residents are not officially recognised by the government. Progress is also hampered by the gatekeepers. Their income – and power – stems from controlling rent, service connections and collecting the monthly dues. It is not within their interests to facilitate the transition to a legal system. Residents find themselves trapped in a poverty cycle.

Photo Source: Henrietta

Facilitating finance flows

While there are many overlapping challenges at play, one major obstacle to the implementation of climate-related human rights standards is economic. Investing in secure and safe basic services for the slums could improve the health, safety and quality of life for many, particularly in the short term whilst more permanent solutions to climate displacement are evaluated.

Financing of such infrastructure needs should be addressed via loss and damage (L&D) mechanisms now, not at an abstract time in the future. Here, however, the international community is stalling – especially concerning after COP26 offered plentiful opportunities to make L&D investment a reality through the Warsaw International Mechanism.

Towards a long-term solution

Ultimately, gaining legal access to basic utilities in temporary settlements is a short-term solution to a long-term challenge. Temporary settlements in these slums are by definition exactly that – temporary. Because of the unplanned nature of the arrival, life there is uncertain and unsafe. “We just want a permanent home,” says one resident in Kallyanpur slum. “When we sleep, we do not really sleep, because we have a fear of eviction.”

When asked about levels of involvement in processes from utilities access to climate-linked mobility planning, residents report experiencing top-down decision-making, contrasted with a passionate determination to participate, and frustration with the status quo: “We want to participate and we want to tell them our experiences. We don’t have a way to do that right now.”

Photo Source: Henrietta

Evolving the concept of migration as adaptation

Broadly speaking, human mobility falls into three categories: migration (predominantly voluntary); displacement (predominantly reactionary, or forced); and planned relocation (17) – which could still be considered reactionary, but implies better management. Planned relocation sees households moving together rather than separating, with the hope to maintain community connections, languages and cultures (18).

Notwithstanding the complex causality of human mobility, forced climate displacement is increasing. Concurrently, the concept of migration as adaptation has been gaining traction in the international development community: the idea of climate migration as a positive, proactive mechanism (rather than a last resort) by which communities can build resilience and diversify livelihoods. However the reality of slum residents’ lived experience sits in contrast to how this is currently being framed. While valid, the concept lacks nuance in a few crucial areas (19).

Firstly, it does not make an adequate distinction between the different types of human movement, and by extension their associated human rights, choice, and agency implications. By not acknowledging that the majority of climate-linked mobility is happening in a forced capacity, a gap in support mechanisms is created.

Secondly, the preferences and needs of the people concerned are not being taken into account: despite a drive to participate, life for a slum resident is one of limited representation and opportunities to self-advocate.

A framework for a participatory approach to climate mobility programme design, as recommended in treaties such as the Nansen Initiative, with detailed plans for both voluntary and forced movement, would be a valuable step towards providing more comprehensive support and protection for this burgeoning demographic. For example, it could help build a picture of which instances of forced displacement could, become re-categorised under ‘planned relocation’ –reactionary movement, but with a higher level of individual and community agency due to increased participation in the planning process.

Citations:

Citations:

- (2021) Access to a healthy environment, declared a human right by UN rights council . https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/10/1102582[Accessed 15 June 2022].

- (2021) Ecological Threat Register 2021.

- Thomas, D. S. G. & Twyman, C. (2005) Equity and justice in climate change adaptation amongst natural-resource-dependent societies. Global Environmental Change. 15 (2), 115-124. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.10.001.

- (2022) Climate Inequality Report 2021.

- Displacement Solutions. (n.d.) About the Bangladesh HLP Initiative. https://displacementsolutions.org/ds-initiatives/climate-change-and-displacement-initiative/bangladesh-climate-displacement/[Accessed 15 June 2022].

- (2008) Migration and Climate Change.

- Piguet, E. (2008) New issues in refugee research: climate change and forced migration. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Climate Change. 1 (4), 517-524. 10.1002/wcc.54.

- See 4.

- Shahadat Hossain Lipu, M., Jamal, T. & Ahad Rahman Miah, M. (2013) Barriers to energy access in the urban poor areas of Bangladesh: Analysis of present situation and recommendations. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy. 3 (4), 395-411. https://doaj.org/article/7ad6832307344cea8152aede672416b3.

- Baser, S., Nahar, S. & Rahman, M. M. (2020) Inequality in Household Resources and Amenities in Dhaka City: The Case of Dhanmondi, Pallabi, and Kallayanpur. The Dhaka University Journal of Earth and Environmental Sciences. 9 (1), 49-62. 10.3329/dujees.v9i1.54861.

- Top of Form

- Bottom of Form

- World Bank. (2018) Population living in slums (% of urban population) – Bangladesh. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS?locations=BD[Accessed 15 June 2022].

- Srishty, M. R. (2021) Cooling down lethal living. https://www.tbsnews.net/thoughts/cooling-down-lethal-living-216370[Accessed 19 June 2022].

- Alam, R., Quayyum, Z., Moulds, S., Radia, M. A., Sara, H. H., Hasan, M. T. & Butler, A. (2021) Dhaka City Water logging Hazards: Area Identification and Vulnerability Assessment through GIS-Remote Sensing Techniques. Research Square Platform LLC.

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. (2012) National Strategy for Water and Sanitation: Hard to Reach Areas of Bangladesh.

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. (2020) Pro-Poor Strategy for Water and Sanitation Sector in Bangladesh.

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. (2016) National Housing Policy.

- Zickgraf, C. (2019) Keeping People in Place: Political Factors of (Im)mobility and Climate Change. Social Sciences (Basel). 8 (8), 228. 10.3390/socsci8080228.

- Randall, A. (2021) Action on climate-linked migration and displacement Empowering refugee and migrant-led organisations .

- (2022) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg2/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FinalDraft_FullReport.pdf[Accessed 09 May 2022].

About the Authors

Karen Makuch, Senior Lecturer, Centre for Environmental Policy, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Imperial College London

Henrietta Hunter, MSc candidate, Environmental Technology (Global Environmental Change and Policy), Imperial College London; Visiting researcher, ICCCAD

Md. Lutfor Rahman, Research officer, ICCCAD